Stress Hormones

Stress hormones are released in response to a stressful situation. This could be a near-miss car accident, a project deadline at work, or overdue bills—any event where our unconscious deems we are in a threatening situation. Before we are even aware, our sympathetic nervous system triggers our fight, flight, or freeze response, and a flood of stress hormones enters our bloodstream. The two primary stress hormones are epinephrine (adrenaline) and cortisol.

The Stress Response

It all starts in our hypothalamus, a small portion of our old “survival brain”. When we encounter a perceived threat—such as a large dog barking at us during a morning walk—our hypothalamus sets off an alarm system in our body. Through a combination of nerve and hormonal signals, the HPA axis (hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal) system prompts our adrenal glands, located on top of our kidneys, to release a surge of stress hormones, including adrenaline and cortisol.

Adrenaline (epinephrine) Stress Hormone

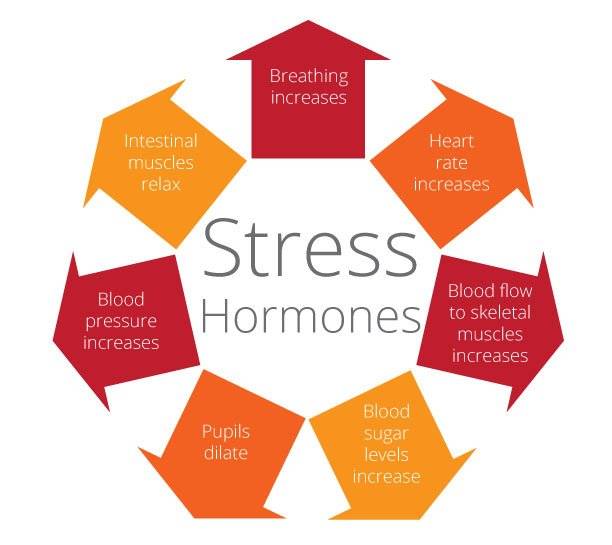

Immediately upon the recognition of a stressor, the amygdala signals the brain stem to release norepinephrine and epinephrine, aka adrenaline. Adrenaline increases our heart rate, elevates our blood pressure, makes us sweat, dialates our pupils, and boosts energy supplies to our muscles, fueling us to fight or flee. Adrenaline causes inflammation in an attempt to destroy antigens, pathogens, or foreign invaders.

Cortisol Stress Hormone

A surge of cortisol follows the release of adrenaline and can remain elevated for hours. Cortisol increases the availability of blood sugars (glucose) in the bloodstream, enhances our brain’s use of glucose, and increases the availability of cells that repair tissues (in case we get hurt as we fight or flee). Cortisol also curbs functions that would be nonessential or detrimental in a fight-or-flight situation, altering the immune system responses and suppressing the digestive system, reproductive system, and growth processes to prioritize survival.

Cortisol’s role in our body and brain isn’t only in response to a stressor, however. It manages how our body uses carbohydrates, fats, and proteins, and communicates with the brain regions that control mood, motivation, and fear. The hormone is integral in controlling our sleep/wake cycle, naturally rising and fall throughout our circadian day, peaking in the morning, and waning throughout the day. Cortisol helps us focus, problem solve, and manage the details of our life, regulates blood pressure, and also boosts our energy when required by controlling blood sugar. It’s a versatile hormone and when in balance, actually decreases inflammation to allow for the effective management of stress [1].

Healthy Stress: The Acute Stress Cycle

Stress takes a variety of forms. Some stress happens as the result of a single, short-term event such as having an argument with a loved one. Other stress relentlessly builds due to recurring conditions, such as managing a long-term illness or a demanding job. When stress hormones are released due to acute, or sudden and short-lived, stressful situations, they rarely have a damaging effect on our bodies. In fact, the right amount of physical stress helps us grow muscle and bone, and being challenged mentally to learn a new task helps us become more effective and efficient.

Following a stressful situation, our body needs to enter a state of relaxation to recover. The parasympathetic nervous system takes over at this point and promotes a “rest and digest” state that returns stress hormone levels back to normal. This is called the Acute Stress Cycle.

Historically, stressors were life-threatening things like predators, famine, and extreme weather conditions. They were present in our lives, but occurred periodically, allowing for the full Acute Stress Cycle to occur and hormonal balance to be restored.

So, as long as our mental, physical and emotional stressors come and go throughout our day, and the sense of perceived threat relaxes after an event, our acute stress cycle is incorporated into our day-to-day life without adverse effects on our balanced health.

Unhealthy Stress: Chronic Stress

When recurring conditions trigger stress that is both intense and sustained over a period of time, it can be referred to as “chronic” or “toxic” stress. While all stress triggers physiological reactions, chronic stress is specifically problematic because of the significant harm it can do to the functioning of the body, brain, and nervous system.

Unfortunately, in our current culture, we now have mental and emotional stress on top of the physical, causing a stress response in situations that aren’t life-threatening—and these situations arise daily; we stress about work drama, our finances, the accomplishments of people we follow on Social (and what we’re not accomplishing in comparison), and so much more. This results in a constantly activated stress response, and constantly elevated levels of our stress hormones, especially cortisol. We rarely have enough of a break between stressors to allow our body to regain hormonal balance. This chronic stress is killing us.

As mentioned above, under normal conditions, cortisol reduces cellular inflammation. However, when continuously secreted due to chronic stress, cortisol fails to function and it actually has the opposite effect—it increases inflammation. This is similar to what happens with insulin resistance in diabetes, where excessive secretion leads to dysfunction. According to the Mayo Clinic, the CDC, and others, chronic stress, and the constant elevation of the stress hormone cortisol causing inflammation, is responsible for a vast majority of the diseases and illnesses of our time, up to 90%.

The Effects of Chronic Stress

Chronic low-level stress keeps the HPA axis activated. This nervous and hormonal system vigilance is much like a motor that is idling too high for too long. Chronic stress leads to:

Inflammation

Repeated stress is a major trigger for persistent inflammation in the body. The brain is normally protected from circulating molecules by a blood-brain barrier. But under repeated stress, this barrier becomes leaky, and circulating inflammatory proteins can damage brain tissue. Chronic inflammation can also lead to a range of health problems, including diabetes and heart disease. Inflammation is one of the leading causes of dementia-related brain diseases like Alzheimer’s.

Anxiety and Depression

The ventromedial prefrontal cortex, which plays a role in emotional cognition – such as evaluation of social connections and learning about fear may enhance irrational fears. Eventually, these fears essentially override the brain’s usual ability for rational decision-making. It has long been researched that chronic stress can lead to depression, which is a leading mental illness worldwide. It is also a recurrent condition – people who have experienced depression are at risk for future bouts of depression, particularly under stress. There are many reasons for this, and they can be linked to changes in the brain. The reduced hippocampus that persistent exposure to stress hormones and ongoing inflammation can cause is more commonly seen in depressed patients than in healthy people. Chronic stress ultimately also changes the neuro transmitting chemicals in the brain that modulate cognition and mood.

Reduced Serotonin levels

Serotonin one of our feel-good hormones is lower in the brain in people with depression. Serotonin is produced in our intestines by the digestion of fiber by our positive gut bacteria, and travels up the vagal nerve to the ‘old brains’. According to the American Psychological Association, stress can affect this brain-gut communication and may trigger pain, bloating, and other effects from inflammatory bowel diseases. The gut’s nerves and bacteria strongly influence the brain and vice versa.

Impaired cognitive performance and brain health

The hippocampus is a critical region for learning and memory and is particularly vulnerable. Studies in humans have shown that inflammation can adversely affect brain systems linked to motivation and mental agility. According to several studies, chronic stress impairs brain function in multiple ways. It can disrupt synapse regulation, resulting in the loss of sociability and the avoidance of interactions with others which limits our choices for de-stressing through co-regulation with others.

Stress can kill brain cells and even reduce the size of the brain. Specifically, chronic stress has a shrinking effect on the prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain responsible for decision making. “Cortisol is believed to create a domino effect that hard-wires pathways between the hippocampus and amygdala in a way that might create a vicious cycle by creating a brain that becomes predisposed to be in a constant state of fight-or-flight,” Christopher Bergland writes in Psychology Today.

Increased abdominal fat and weight gain

Elevated cortisol levels create physiological changes that help to replenish the body’s energy stores that are depleted during the stress response. Unutilized for flight or fight, that extra available glucose gets stored as fat.

Hyperglycemia (blood sugar imbalance), metabolic syndrome, and Type 2 Diabetes.

Research suggests that chronic stress may also contribute to obesity, both through direct mechanisms (causing people to eat more) or indirectly (decreasing sleep and exercise), Type 2 Diabetes, and Metabolic Syndrome.

Heart disease

Persistent epinephrine surges can damage blood vessels and arteries, increasing blood pressure and raising the risk of heart attacks or strokes.

Compromised immune system

While this is valuable during stressful or threatening situations where injury might result in increased immune system activation, chronic stress can result in impaired communication between the immune system and the HPA axis. This impaired communication has been linked to the future development of numerous health conditions, including chronic fatigue, fibral myalgia, and immune disorders. Even Autoimmune disorders are created as an inflammatory response to ongoing stress. The immune system becomes overly sensitized to the body’s own healthy cells and tissue. It reacts against the joints, intestines, or other organs and tissues as if they were dangerous. As the inflammatory response continues, it damages the body instead of healing it.

Muscle atrophy, decreased bone density, and hormone imbalance

Experiencing stressors over a prolonged period of time can result in a long-term drain on the body. As the autonomic nervous system continues to trigger physical reactions, it causes a wear-and-tear on the body. It’s not so much what chronic stress does to the nervous system, but what continuous activation of the nervous system does to other bodily systems that become problematic. Constant cortisol production from our Adrenal glands lowers the production of DHEA, the precursor to our male and female sex hormones. The resulting decline in testosterone production negatively affects libido, and can even cause erectile dysfunction or impotence. Women who are more stressed and anxious may experience an increased number, intensity, and severity of hot flashes, according to the American Psychological Association.

Increased likelihood of addiction

A series of population-based and epidemiological studies done at Yale University School of Medicine proves that increased levels of cortisol is predictive of substance use and abuse. Preclinical research also shows that stress exposure enhances drug self-administration and reinstates drug-seeking in drug-experienced animals (addiction).

Insomnia

Naturally, cortisol wanes throughout the day and is replaced with our sleep-beckoning hormone melatonin. Elevated cortisol levels late into the day stimulates us and prevent melatonin from being released, impacting our circadian rhythm and making it harder to fall asleep and stay asleep. Unfortunately, researchers at Dartmouth have proven that is a negative cycle, “sleep, in particular deep sleep, has an inhibitory influence on the hypothalamic-pituitary- adrenal (HPA) axis, whereas activation of the HPA axis or administration of glucocorticoids can lead to arousal and sleeplessness. Insomnia, the most common sleep disorder, is associated with a 24-hour increase of ACTH and cortisol secretion, consistent with a disorder of central nervous system hyperarousal”. Increased stress leads to poor sleep, and poor sleep, in turn, leads to increased stress. We must learn to break the cycle.

Read our Sleep Hygiene Checklist for your best night’s sleep.

With such a dramatic effect on our health, how we deal with and react to stress, and learning how to prevent or lessen the impact of our stress response is critical to our health and longevity.

Getting to the bottom of Stress-induced Disease

Humans, like all animals, are genetically wired to cope with environmental stressors for survival. How harmful a physical, mental, or emotional stressor is, ultimately depends on its intensity, duration, integration, and, as the most recent research is concluding, how our autonomic nervous system was developed as a child. If we had traumatic events, neglect, developmental attachment issues, or toxic shame in our childhood, our brain, and nervous system will have developed a low-grade survival vigilance. That underdeveloped or under-resourced response will keep cortisol amplified daily decades later. This can put many of us under more stress than may seem necessary.

Emerging Stress Patterns

Before the Covid pandemic, the Stress in America survey reported that money and work were the top two sources of stress for adults in the United States for the eighth year in a row. Other common contributors included family responsibilities, personal health concerns, health problems affecting the family and the economy. The study found that women consistently struggle with more stress than men. Millennials and Gen Xers deal with more stress than Baby Boomers. And those who face discrimination based on characteristics such as race, religion, poverty, disability status, or LGBTQ identification, struggle with more stress than their counterparts who do not regularly encounter such societal biases.

Vagal Theory

A recent study conducted by Stephen Porges, the guru on poly-vagal theory (our autonomic survival nervous system), found that during Covid, the most highly stressed individuals (who weren’t infected) were those who had either an underdeveloped or underregulated/underresourced survival and safety nervous system. Vagal Tone describes our nervous system’s ability to co-regulate with others through prosocial interactions, and self-regulate through practices that induce the parasympathetic (rest and digest) nervous system. Decreases in vagal tone is associated with illnesses and complications that affect our nervous, circulatory, respiratory, and digestive systems as all of our internal organs are connected to the ‘many wandering’ strands of the polyvagal nerve that connects to our reticular, limbic, and neo-cortex brains.

How To Manage Chronic Stress

Since there will always be stressful events in our lives, with all of these varied symptoms of chronic stress on our Balanced Health, what can we do?

Elicit the ventral vagal parasympathetic relaxation response

Harvard Health reports, Dr. Herbert Benson, director emeritus of the Benson-Henry Institute for Mind-Body Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, has devoted much of his career to learning how people can counter the stress response by using a combination of approaches that elicit the ventral vagal parasympathetic relaxation response. These include deep abdominal breathing, focus on a soothing word (such as “peace” or “calm”), visualization of tranquil scenes, repetitive prayer, yoga, and tai chi.

Practice mindfulness and journal

You can learn to identify what stresses you and how to take care of yourself physically and emotionally in the face of stressful situations through mindful reflection and journalling. When practicing mindfulness meditation, heart rate and breathing slow down, blood pressure normalizes, adrenal glands produce less cortisol and immune function improves. The mind also clears, and creativity increases. Additionally, mindfulness will prevent stress levels from reaching an extreme, or getting out of control. This will allow the Acute Stress Cycle to complete more frequently, resting and digesting fully following a stressful event.

Resource Your Body, Mind, and Spirit to Restore Stress Hormone Levels Quicker

Stress is naturally draining. Resourcing yourself following a stressful experience will restore the balance of your stress hormones and prevent the negative effects of chronic stress. Try eating a healthy diet and getting regular exercise and plenty of sleep. Practicing relaxation techniques such as meditation, yoga, deep breathing, getting a massage, taking time for creative hobbies, reading an inspirational book, or listening to emotionally relaxing music. Walking in nature also lowers cortisol and bathes our brain in positive mood stimulating neurotransmitters (dopamine, serotonin, oxytocin). Fostering healthy intimate friendships, engaging a sense of humor, and seeking professional Relational Somatic Therapy to expand our “window of tolerance” for external stressors that may trigger our autonomic /survival response patterns from childhood help us self-regulate. Resourcing habits between acute stress ‘demands’ and co-regulation with safe others coupled with self-regulation techniques all help break the cycle of chronic stress, nervous system vigilance, constant cortisol elevation, and disease-causing inflammation.

Purposefully Expose Yourself to Acute Stress

Intentionally putting ourselves in stress-inducing, but not harmful or damaging, situations can desensitize our stress response and improve our longevity. Activities such as intermittent fasting or cold-immersion are stressful by definition but performed correctly, they are not harmful and in fact, have a long list of health benefits. Intermitting fasting has been proven to cause cellular autophagy, a process of cellular healing, and Caloric restriction (CR), the reduction of calorie intake to a level that does not compromise overall health, has been considered as being one of the most promising dietary interventions to extend lifespan in humans.

Cold water immersion has a vast array of benefits, from raising metabolic rate by 350%, lowering Cortisol by 46%, raising noradrenaline by 530%, and raising dopamine by 250%. Pain and inflammation also decrease (as experienced in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia due to increased production of opioid endorphins in the body). Research has shown that cold showers or cold immersion create a “positive systemic stress activation”, through which the high density of cold receptors on the skin sends an overwhelming amount of electrical impulses to the brain. This positive transient activation ignites the sympathetic nervous system and HPA axis (Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal-Thyroid nervous and hormonal systems). This activation has immense stimulating effects on our immune system by promoting lymphatic drainage! Brief daily cold stress increases the production of T-Lymphocyte, also known as T-cells, a type of leukocyte (white blood cell), and Natural Killer cell, also known as NK cell, production and activation. Both are critical in our immune system. Research is proving the benefits of cold water immersion in innate tumor immunity and nonlymphoid cancer survival rates.

What is Mountain Trek?

Mountain Trek is the health reset you’ve been looking for. Our award-winning hiking-based health program, immersed in the lush nature of British Columbia, will help you unplug, recharge, and roll back years of stress, anxiety, and unhealthy habits. To learn more about the retreat, and how we can help you reset your health, please email us at info@mountaintrek.com or reach out below: